Each year, Briggs & Stratton, the self-proclaimed world’s largest producer of air-cooled gasoline engines for outdoor power equipment, holds an All-American Lawn contest. For some reason they’ve decided that I need to know about this event, and every year they send me an elaborate press kit, complete with fact sheets and glossy photographs.

Usually the contest is open to ordinary people who just happen to have five or ten acres of golf course-like greens around their house. The grand prize winner gets ten thousand dollars (yep, you read that right—grass is big business), and the runners-up get a one thousand dollar gift certificate to a home improvement store. If you don’t have a lawn worthy of the All-American Lawn grand title, you can still enter the Chance Drawing. Winners of the Chance Drawing get a free visit from a Briggs & Stratton Lawn Doctor to help them whip their turf into shape.

One year, Briggs & Stratton decided to honor ten public lawns. They chose lawns that reflected the spirit of our great nation: “power and influence, pride and competitive spirit, freedom and simplicity.” The American Lawn, they claimed, is “a symbol of the colonial past and a constant ideal in the American-built environment.”

Now, I have never been a fan of lawns—I have ripped lawns out at two houses so far—but I’ll get to that in a minute. First I want you to see what a person is up against when they take a stand against grass. The tradition of a green lawn goes beyond a few suburbanites with their Scot Turf Builder and their riding mowers. This is football-on-Thanksgiving territory, Chevy Suburban-and-Little League territory. In these patriotic times, a person runs a real risk by even questioning the value of The American Lawn.

The top ten public lawn list included the Alamo, the United States Naval Academy, Doubleday Field, and the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center. In case I didn’t grasp the sheer majesty of these public lawns, slides were enclosed. The Alamo, off in the distance, with a smooth green carpet in the foreground. The Naval Academy, where white-clad officers marched on a neatly clipped field. The American Lawn, Briggs & Stratton seemed to claim, has been underfoot in some of our nation’s proudest moments—battles, sporting events, and explorers looking to stake a claim out west.

Briggs & Stratton has carried on this one-sided correspondence with me for years, but it has failed to persuade me. I just don’t see the point of a lawn. Why would anybody take a plant—grass—and plant it by the thousands, only to chop it down to the ground every few weeks? I like plants that contribute something, but lawns produce neither flowers nor fruit. They offer shelter to only a few creatures, and even those inhabitants—worms, crickets, and the like—are put off by the never-ending applications of fertilizer and herbicide. Lawns demand a rather alarming amount of water. In fact, cities like Albuquerque have decided that perhaps the lawn is not so All-American after all and have put ordinances in place that strongly discourage the installation of lawns in new housing developments.

Now, I know some of you will disagree with me on this. “You’ve got to have a lawn,” friends have told me over the years. “Don’t you like to sit outside on the grass?”

Well, I live in Eureka, I explain, where it is almost always chilly and damp. No, when I’m outside, I find it’s best to keep moving.

“Yes, but we’ve got [dogs/children/cats/bunnies] and they need a little grass so they can run around.”

Hmmm. I’m no expert on dogs, but cats are sly creatures who prefer a variety of hiding places and lookout points. An expanse of grass would leave a cat, with all its inexplicable paranoia, far too exposed. As for children, the kids who visit my garden seem to enjoy a world where the flowers are taller than they are and strawberries and cherry tomatoes are just waiting to be picked and eaten.

“But you can’t plant a garden everywhere,” people say. “It’s too much work. Besides, what will the neighbors think?”

All right, now we’re getting to the heart of the matter. When I bought my house, I hired a crew to dig out the lawn, till in some compost, and spread a layer of chipped bark on top. Grass runs in an uninterrupted expanse on my block, from one end of the street to the other, without so much as a driveway to interrupt the flow. At least, that’s how it used to be. Suddenly there was a gash in the middle of this stretch of lawn, and it did occur to me briefly to wonder what the neighbors might think.

But now I get nothing but smiles and compliments when the neighbors walk by. It is, after all, a cheery sight. Daisies and penstemon, lavender and sage, cosmos and pincushion flower, all bloom with abandon where once there was nothing but lawn. And although I’ve never maintained a lawn, I know that my garden must require less work. In fact, all it needs is a little deadheading in summer and fall and a topdressing of compost just before winter. Most of the plants prefer dry conditions in summer, so I don’t even spend much time watering.

If you’ve ever thought about ripping out your lawn, consider these ideas:

Removing the lawn: I dug out the grass because the ground sloped and I needed to do a little leveling of the site anyway. But if this isn’t a problem for you, consider smothering the grass in 2-3 layers of cardboard or 15-20 sheets of overlapping newspaper. Soak the cardboard or newspaper well and top with at least six inches of manure, grass clippings, dried leaves and compost. The paper will decompose eventually and you’ll be left with good, rich soil for planting.

Groundcovers: There are plenty of good groundcover choices at the nursery. You might plant a few of them at the edge of your lawn and pick the one that performs best. Herbs such as yarrow, thyme, and chamomile all make interesting lawn alternatives and can handle light foot traffic.

Perennials: I couldn’t resist planting a jumble of my favorite flowers. But if you want something more…organized, consider planting masses of just one plant, such as lavender, heather, salvia or penstemon. Here are some

great long-blooming choices from White Flower Farm.

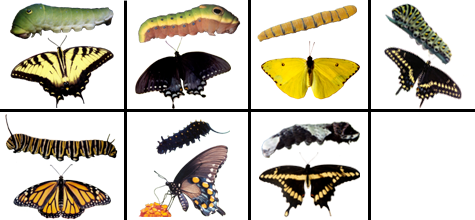

Meadows: A wildflower meadow attracts birds and beneficial insects and demands little in the way of water or fertilizer. Native flowers like poppy and clarkia perform well on their own or in a mix with native grasses. If you’re thinking about turning your yard into a meadow, check out

The Blooming Lawn: Creating a Flower Meadow, by Yvette Verner and

Front Yard Gardens: Growing More than Grass. You can also visit the

California Native Plant Society. Come to think of it, a lawn given over to native wildflowers may be the most All-American lawn of all.

As long as we're on the subject of paintings...my friend Annette (who would like me to point out that she is pregnant, not fat, in these images) in the garden at

As long as we're on the subject of paintings...my friend Annette (who would like me to point out that she is pregnant, not fat, in these images) in the garden at