A couple years ago, I went to visit my cousin Colin in Minneapolis in early spring. As soon as I got into town, I developed all the symptoms of a horrible cold—sore throat, congestion, and headache. Nobody likes a sick houseguest, but I had no choice but to beg Colin to let me crawl into bed and spend my vacation doped up on cold medicine.

A few days later, feeling no better, I thought that I should at least go take a walk along the Mississippi River and see a little of the city. It was a warm, sunny day and all the trees were just beginning to come to life. Colin and I strolled along a trail next to the water, and after a few minutes, I noticed a light dusting of something on my shoulders. “What is this stuff?” I asked.

“Pollen,” she said.

I stopped and stared at her. “Pollen? I’m not sick,” I said. “I’m allergic!”

Sure enough, I had timed my visit to coincide with the glorious spring allergy season in Minneapolis. I’d never considered myself to be particularly prone to allergies, but this time I had met my match.

I’m not alone. About 50 million Americans are affected by hay fever every year. Tom Ogren, author of Allergy-Free Gardening and

Safe Sex in the Garden, has a theory about why so many people suffer: gardeners and landscapers, in an attempt to be tidy, prefer to plant male trees and shrubs. The females drop fruit, leaving a mess all over the sidewalk or the lawn. But a male tree just produces nice little well-behaved flowers—that is, if your definition of “well-behaved” includes spewing plant sperm into the air for weeks on end.

It didn’t help that Dutch Elm Disease wiped out stately old American Elm trees across the country in the 1950s and 1960s. Those trees were perfect flowered, meaning that the trees’ flowers had both male and female parts, and were pollinated by insects, so they shed less pollen. When gardeners, landscapers, and civic groups replaced the diseased trees, they often chose the male varieties of various wind-pollinated trees. That means more pollen blowing around on beautiful spring weekends like the one I suffered through in Minneapolis.

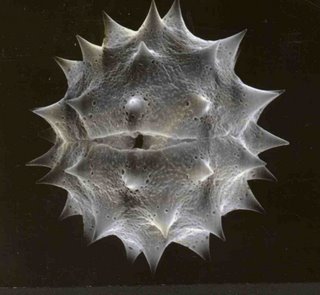

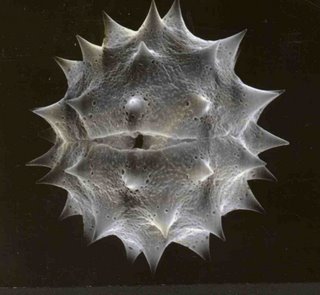

Ogren told me a couple of interesting stories about pollen-producing plants last week. He once knew a family who had a huge male mulberry tree in their garden. One day, when their boy was playing down the street, the father decided to blast the tree with the hose to wash the pollen away. What they didn’t realize, Ogren said, was that when light, buoyant pollen grains get wet, “they suddenly start to germinate. Sometimes you can actually see this happen right before your eyes on a glass microscope slide if you add a drop of water. The outside of the pollen grain (the extine) is allergenic, but the inside (the entine) is much more allergenic, sometimes ten times as much so.” Both the husband and wife felt their throats close shut and had to lock themselves in the bathroom just to be able to breathe. The son spent the night at a friend’s house, and the parents actually spent the night in the bathroom.

Ogren also told me that he’d been at a party a few years ago, and a guy in his mid-twenties told him that allergies were all in people’s heads and that no pollen could make him sneeze. “There just happened to be a large male Deodar Cedar tree in the front yard of that house,” Ogren said, “and it was in full bloom. I told the guy that he was wrong and that enough pollen could make anyone sneeze. He offered to bet me five dollars that I couldn’t find any pollen that would make him sneeze in five minutes.”

He took the guy up on his bet and went outside to shake some pollen onto a piece of paper. “To my surprise,” Ogren said, “he took a crisp twenty dollar bill out of his wallet, rolled it up, and proceeded to snort all of the pollen up his nose!”

The guy didn’t sneeze. Ogren paid him his five bucks. But half an hour later, he found him in the kitchen, splashing water in his nose, sneezing uncontrollably. “I’m told he kept on sneezing for three days,” Ogren said.

Ogren’s two books address the many ways in which a plant can make a person miserable, and for both of them he uses a rating system he developed himself called OPALS (Ogren Plant-Allergy Scale). He rates plants based on the amount of pollen they produce, the duration of their pollen season, and other factors, with ten being the worst. The result is a very helpful set of guides for choosing plants that won’t exacerbate allergies. If anyone in your family is prone to allergies, just evaluating the shrubs and trees that grow near bedroom windows could make a huge difference.

A male date palm, for instance, carries an OPALS rating of nine, while a female is rates a healthy one. (Plant labels don’t identify the sex of a tree, something Ogren would like to change. Ask the staff at your nursery for help choosing a female tree if pollen is a concern.) Other popular plants with high OPALS ratings include fountain grass, male wax myrtles, and junipers. Many of the ornamental shrubs that people plant around their homes around here are low-pollen plants: fuchsia, rhododendron, princess flower, camellia, and salvia are all safe bets.

The bottom line is that your garden doesn’t have to make you miserable. Take charge of the situation. Make your plants behave. To find out more,

check out Ogren’s books or

visit him online.

(photo of feverfew pollen grain courtesy of Dr. Walter H. Lewis)

What they did not have at the show but I am lusting after (damn that print catalog!): Cosmos 'Apricot' if you can believe it...

What they did not have at the show but I am lusting after (damn that print catalog!): Cosmos 'Apricot' if you can believe it... and nasturtium 'Margaret Long,' named after the woman who discovered it in her Irish garden 100 years ago. Margaret, I could kiss you! (Well, not now. But 100 years ago I would have.)

and nasturtium 'Margaret Long,' named after the woman who discovered it in her Irish garden 100 years ago. Margaret, I could kiss you! (Well, not now. But 100 years ago I would have.)